Projects

Conservation and food security implications of large- and small-scale fisheries conflict

Achieving sustainable and equitable fisheries management in an increasingly industrialized ocean is a pervasive challenge for conservation. A major threat to the ecological and social well-being of coastal communities around the world is competition with large, industrial fishing fleets on areas used by small-scale artisanal fisheries. This competition between large- and small-scale fisheries is expected to increase in coming decades as species move in response to climate change, particularly in fishing-dependent communities and in low-income countries. However, the impacts of large-scale fishing in coastal areas are not well-understood. For this project, based at the Coasts and Commons Co-Lab at Duke University in collaboration with Dr. Xavier Basurto and Dr. Elena Finkbeiner, we estimated global vulnerability of coastal fisheries using two recently available global datasets of small-scale and large-scale fishing activity (manuscript in review). Our findings underscore the need to proactively strengthen small-scale fishery access rights and limit industrial overcapacity to mitigate conflicts and make progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals.

This work was supported by a Smith Conservation Research Fellowship and conducted in partnership with the Illuminating Hidden Harvests Project (Duke University, WorldFish, and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization), Conservation International, and Global Fishing Watch.

Building on those findings, we built a collaborative project between ISSF, AZTI, Mobula Conservation, and NOAA’s Pacific Islands Regional Office to test a novel bycatch release tool: the mobulid sorting grid. Deployed on 12 U.S. purse seine vessels in the Pacific, the sorting grid has shown early promise in facilitating the rapid and safe release of mobulids, based on 41 capture events. These results—currently under review—suggest that the tool could be scaled up to improve post-release survival across fleets. Adoption of such devices by tuna fleets and regional fisheries management organizations could help ensure consistent, effective bycatch mitigation for these vulnerable species in tuna fisheries worldwide.

This work was supported by the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation and NOAA’s Pacific Islands Regional Office and conducted in close partnership with AZTI-Tecnalia in Spain.

Manta and devil ray bycatch mitigation in tuna fisheries

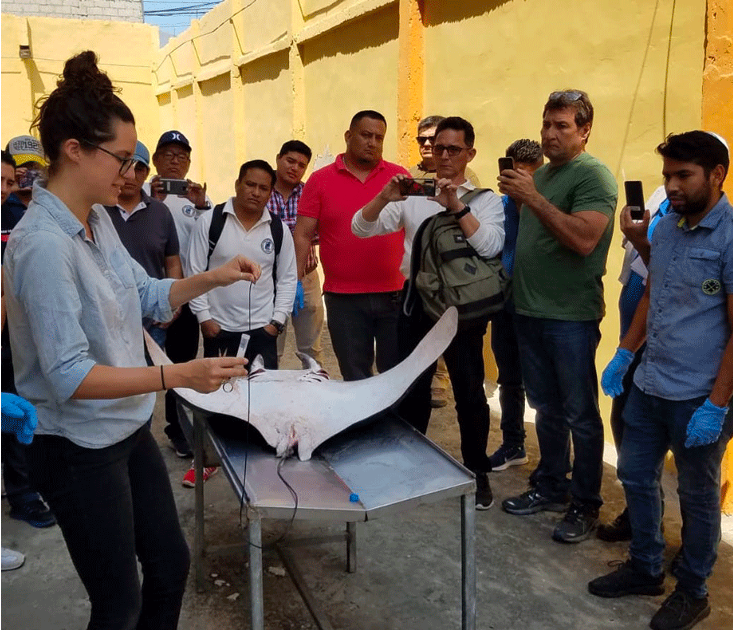

Manta and devil rays (mobulids) are globally threatened species that frequently interact with tropical tuna purse seine fisheries, where an estimated 13,000 individuals are caught as bycatch each year (Croll et al., 2016). In collaboration with the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation, The Manta Trust, and TUNACONS, I led a study to work with tuna vessel crews in the Eastern Pacific Ocean to identify key barriers to safe mobulid release and surface fisher-informed solutions (Cronin et al., 2022 ICES Journal of Marine Science). Using surveys and focus groups, we found that most mobulids are only visible to fishers after capture—underscoring the need for post-capture interventions—and that existing gear often lacks the equipment needed for safe release of large individuals. That research provided a model for incorporating fisher knowledge into the design of bycatch mitigation strategies for mobulids.

Conservation genetics of manta and devil rays

To support more targeted conservation strategies for mobulids, we are investigating their population structure and genetic diversity across the Pacific. In partnership with the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission and the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation, we worked with fisheries observers and crew to collect tissue samples at sea from individuals bycaught in tropical tuna fisheries. Using genome-wide sequencing (RADseq), we analyzed over 25,000 genetic markers from individuals spanning four regions in the Pacific, with Indian Ocean samples included for comparison. Our findings reveal subtle but significant population structure, as well as signs of geographically localized adaptation in manta and devil rays and offer critical guidance for designing conservation measures that preserve evolutionary potential and population health.

This project was supported by a National Geographic Explorers Grant, the Save Our Seas Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and a Switzer Foundation Fellowship.

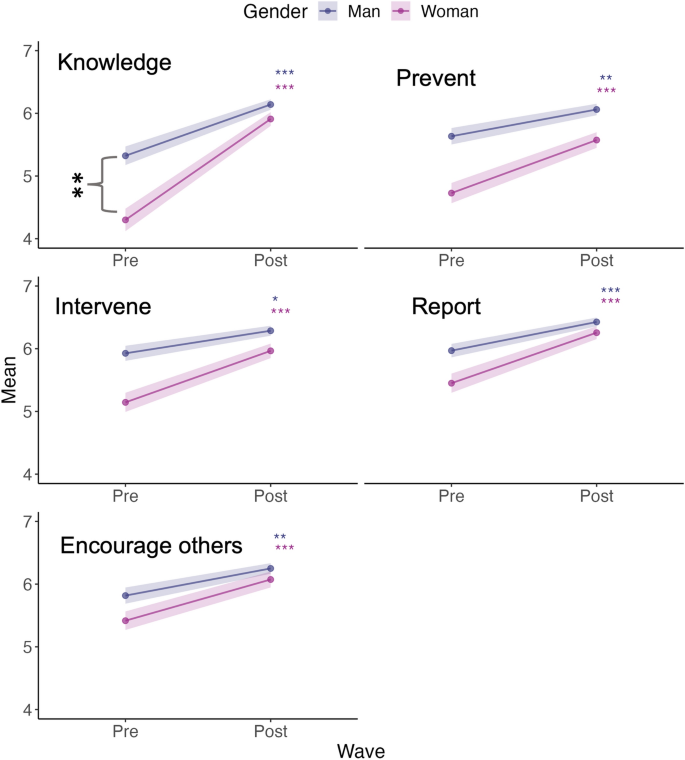

Improving fieldwork safety through prevention training

To support more targeted conservation strategies for mobulids, we are investigating their population structure and genetic diversity across the Pacific. In partnership with the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission and the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation, we worked with fisheries observers and crew to collect tissue samples at sea from individuals bycaught in tropical tuna fisheries. Using genome-wide sequencing (RADseq), we analyzed over 25,000 genetic markers from individuals spanning four regions in the Pacific, with Indian Ocean samples included for comparison. Our findings reveal subtle but significant population structure, as well as signs of geographically localized adaptation in manta and devil rays and offer critical guidance for designing conservation measures that preserve evolutionary potential and population health.

This project was supported by a National Geographic Explorers Grant, the Save Our Seas Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and a Switzer Foundation Fellowship.

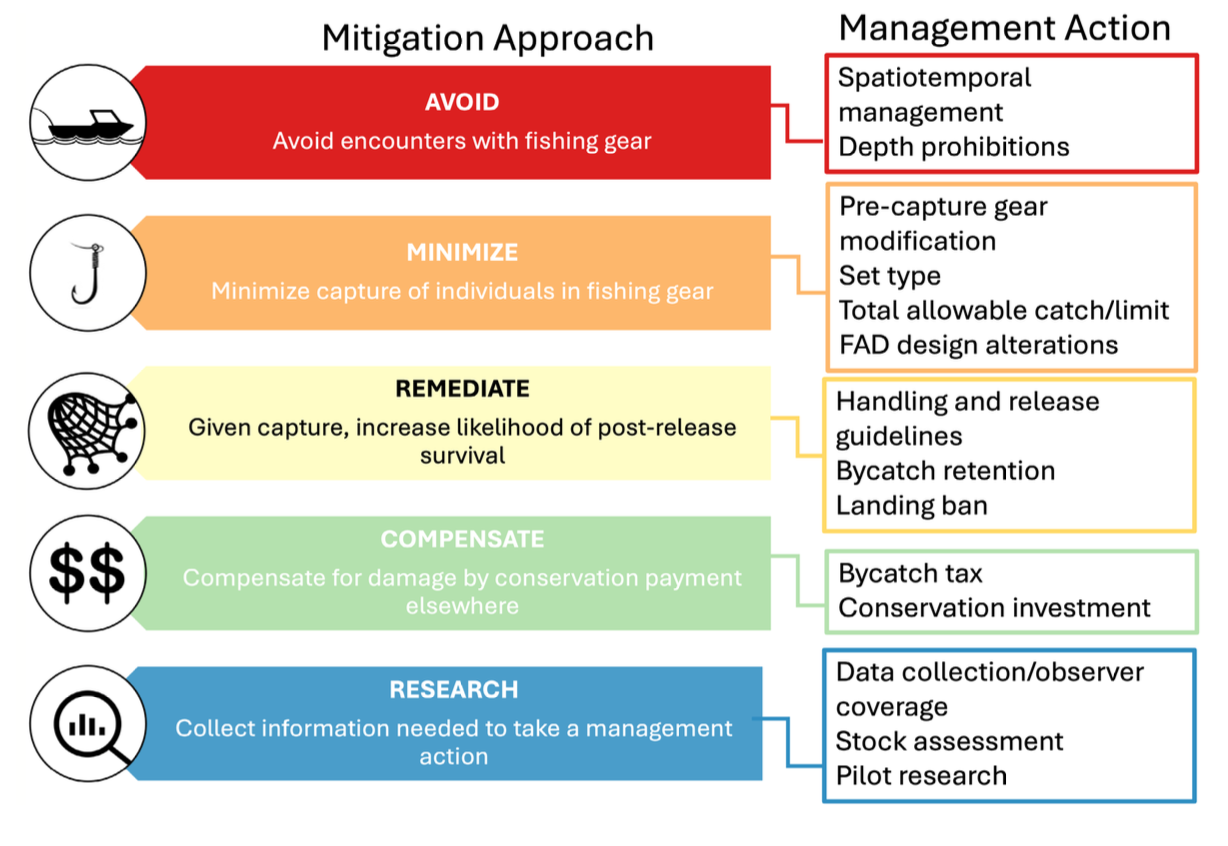

Shark and ray conservation policy in industrial tuna fisheries

Pelagic sharks and rays are among the most threatened megafauna in global tuna fisheries, yet current policies by tuna Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (tRFMOs) fall short of preventing their incidental capture. In this study, we analyzed all active tRFMO policies targeting elasmobranch bycatch and found that the vast majority focus on post-capture measures rather than avoidance (Cronin et al., 2022, Fish and Fisheries). Despite a strong emphasis on research mandates, policy adoption has not historically aligned with the availability of scientific evidence. These findings suggest that stronger data alone will not drive policy change. Instead, we recommend structural reforms to tRFMO governance, including binding bycatch limits and precautionary measures to protect threatened species. This work underscores the need for more ambitious, enforceable policies to reduce the ecological impact of industrial tuna fisheries on vulnerable elasmobranchs.